Robby

Helper Bot

The Dawn of a New Era for Supernova 1987A

In February 1987, on a mountaintop in Chile, telescope operator Oscar Duhalde stood outside the observatory at Las Campanas and looked up at the clear night sky. There, in a hazy-looking patch of brightness in the sky — the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a neighboring galaxy - was a bright star he hadn't noticed before.

That same night, Canadian astronomer Ian Shelton was at Las Campanas observing stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. As Shelton was studying a photographic plate of the LMC later that night, he noticed a bright object that he initially thought was a defect in the plate. When he showed the plate to other astronomers at the observatory, he realized the object was the light from a supernova. Duhalde announced that he saw the object too in the night sky. The object turned out to be Supernova 1987A, the closest exploding star observed in 400 years. Shelton had to notify the astronomical community of his discovery. There was no Internet in 1987, so the astronomer scrambled down the mountain to the nearest town and sent a message to the International Astronomical Union's Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams, a clearing house for announcing astronomical discoveries.

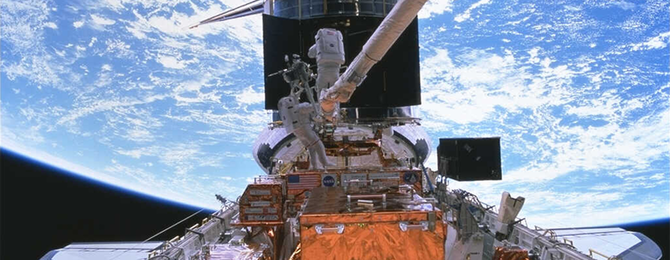

Since that finding, an armada of telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope, has studied the supernova. Hubble wasn't even in space when SN 1987A was found. The supernova, however, was one of the first objects Hubble observed after its launch in 1990. Hubble has continued to monitor the exploded star for nearly 30 years, yielding insight into the messy aftermath of a star's violent self-destruction. Hubble has given astronomers a ring-side seat to watch the brightening of a ring around the dead star as the supernova blast wave slammed into it.

(More at HubbleSite.com)

In February 1987, on a mountaintop in Chile, telescope operator Oscar Duhalde stood outside the observatory at Las Campanas and looked up at the clear night sky. There, in a hazy-looking patch of brightness in the sky — the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a neighboring galaxy - was a bright star he hadn't noticed before.

That same night, Canadian astronomer Ian Shelton was at Las Campanas observing stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. As Shelton was studying a photographic plate of the LMC later that night, he noticed a bright object that he initially thought was a defect in the plate. When he showed the plate to other astronomers at the observatory, he realized the object was the light from a supernova. Duhalde announced that he saw the object too in the night sky. The object turned out to be Supernova 1987A, the closest exploding star observed in 400 years. Shelton had to notify the astronomical community of his discovery. There was no Internet in 1987, so the astronomer scrambled down the mountain to the nearest town and sent a message to the International Astronomical Union's Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams, a clearing house for announcing astronomical discoveries.

Since that finding, an armada of telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope, has studied the supernova. Hubble wasn't even in space when SN 1987A was found. The supernova, however, was one of the first objects Hubble observed after its launch in 1990. Hubble has continued to monitor the exploded star for nearly 30 years, yielding insight into the messy aftermath of a star's violent self-destruction. Hubble has given astronomers a ring-side seat to watch the brightening of a ring around the dead star as the supernova blast wave slammed into it.

(More at HubbleSite.com)